Today more than ever before, people in western societies can go through life without encountering serious talk about God. Many probably never suspect that Christianity had a unique and essential role in forming many of the values and social institutions that we enjoy today. But it did. And it is useful for Christians to have a basic understanding of this for the sake of engaging our non-Christian friends who assume that Christianity has never done anything good for the world.

This week the Centre for Public Christianity (CPX) hosted their annual Richard Johnson Lecture, a series that aims to ‘highlight Christianity’s relevance to society and positively contribute to public discourse on key aspects of civil life.’ This year’s speaker was Nick Spencer, Research Director of Theos Think Tank in London. Spencer’s theme was ‘Where did I come from? Christianity, Secularism, and the Individual’. His talk was engaging and insightful, and I recommend that you listen to it.

Enlightenment Myths

Spencer began by describing Steven Pinker’s latest book, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018). As the title suggests, Pinker is an enthusiastic promoter of the values of the 18th Century Enlightenment and its central concern with the authority of reason, as opposed to that of religion or tradition. Pinker believes that the Enlightenment is what lay behind basically everything good in modern western civilisation.

Practically all of the institutions that led to peace, prosperity and freedom came into being before the Enlightenment, and mostly within Christian cultures

Spencer demonstrated how untrue this characterisation is. Whilst the Enlightenment produced many remarkable achievements, practically all of the institutions that led to peace, prosperity and freedom came into being before that time, and mostly within Christian cultures. But Spencer also provided Christians with a timely warning not to overstate our case as Pinker does. We should be equally wary of the claim that everything good in western culture comes from Christianity. Spencer urged people to distinguish what comes out of distinctly Christian ideas from what merely comes out of Christian cultures.

Distinctly Christian Ideas

That said, Christianity is rightly identified as the cause of many good things that we take for granted. Spencer highlighted four in particular. First, political authority. The notion that authority is not just the application of raw power is not an intuitive idea. Christianity taught us that power only becomes authority (legitimate power) when it is exercised in accordance with law. Second, the rule of law. By long reflection on the laws of the Old Testament, society learned that law is what rightly regulates society. Third, the emergence of secular political space. God has designated the present time (Latin: saeculum) as a distinct era with its own character of being prior to second-coming of Jesus. That means that there is a proper place for ‘this-age’ politics that are not identical to the politics of the coming Kingdom of God but can be challenged if they become despotic. Fourth, the idea of toleration. Spencer highlighted that even the great Enlightenment thinker John Locke (1632-1704) based his influential views on tolerance on biblical ideas.

Christianity taught us that power only becomes authority (legitimate power) when it is exercised in accordance with law.

Undergirding all of this is a more foundational Christian idea, namely the biblical view that all human beings are equal in God’s sight and must be treated that way. This view was especially the result of reflection on the fact that God’s Son became a human being of the most ordinary social status.

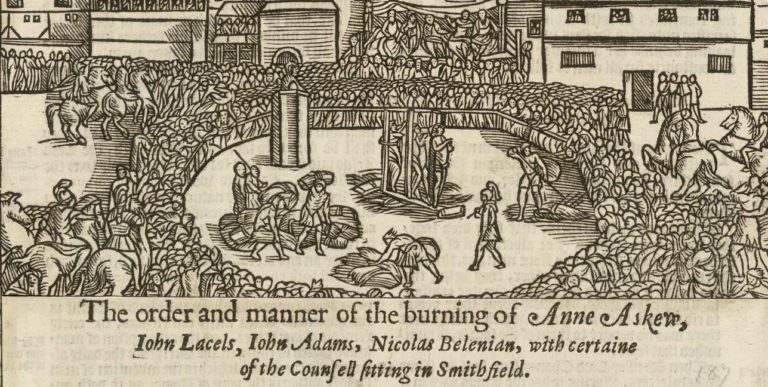

Spencer’s presentation was winsome and non-combative. He presented Christian truths clearly and persuasively, whilst also recognising that history is messy and complicated and that Christians have often failed to live out their own values. The lecture was permeated with a mood of realism: realism about the how Christian ideas have transformed society, as well as realism about the way Christians have often failed to live out these ideas consistently or have believed that the Bible taught things that we should regard as highly regrettable at best.

Critical Reflection

For all my appreciation of Spencer’s lecture, I have two points of criticism.

First, Spencer recognised that Christians have often disagreed about what the Bible means, however he didn’t reflect on the fact that not all readings of the Bible are equally legitimate. He seemed to accept the notion that people can get whatever they want from the Bible rather than label the fact that people often distort it (2 Peter 3:16). Just as Spencer sought to be understood in his lecture, so God expects to be understood in the Bible. Whilst we should recognise that biblical interpretation is often challenging, we shouldn’t feign away from identifying where we believe that the Bible has been misused so I believe this point should have been made explicitly.

Secondly, for me the lecture highlighted both the potential and the danger of seeking to promote Christianity in an intellectually respectable way. The final question of the night was: “what is Christianity’s greatest gift to society?’ Spencer answered by reiterating the conclusion of his talk, essentially highlighting the concept of the value of all human beings. This idea is certainly of incalculable importance, however that is not the correct answer to the question. My concern is that in seeking to promote Christianity intellectually, it is very easy to play by the rules of the intellectual game and find ourselves highlighting abstract ideas rather than the gospel itself.

The greatest gift of Christianity to society is Jesus Christ. But he’s not a gift that Christians give society. Jesus is the gift that God gave, whom we gratefully receive, and who we invite others to receive along with us. The wonderful effects of the gospel in inspiring values and institutions that promote human flourishing are wonderful implications of the gospel, but they are just that: implications. In our eagerness to engage our society intellectually we must never lose sight of the fact that whilst the effects of the gospel are winsome, it is only the gospel itself that will ultimately win people over.