A few years ago the whispers started: “Have you… ahh… read… umm… the book by Sheila Wray Gregoire?” I first heard this from a pastor friend, then a mention on a podcast and by the time a few married Christian woman cautiously shared links on social media it was clear others were whispering too. What was this book that so many Christians wanted to (discreetly) talk about? The Great Sex Rescue by Sheila Wray Gregoire.[1]

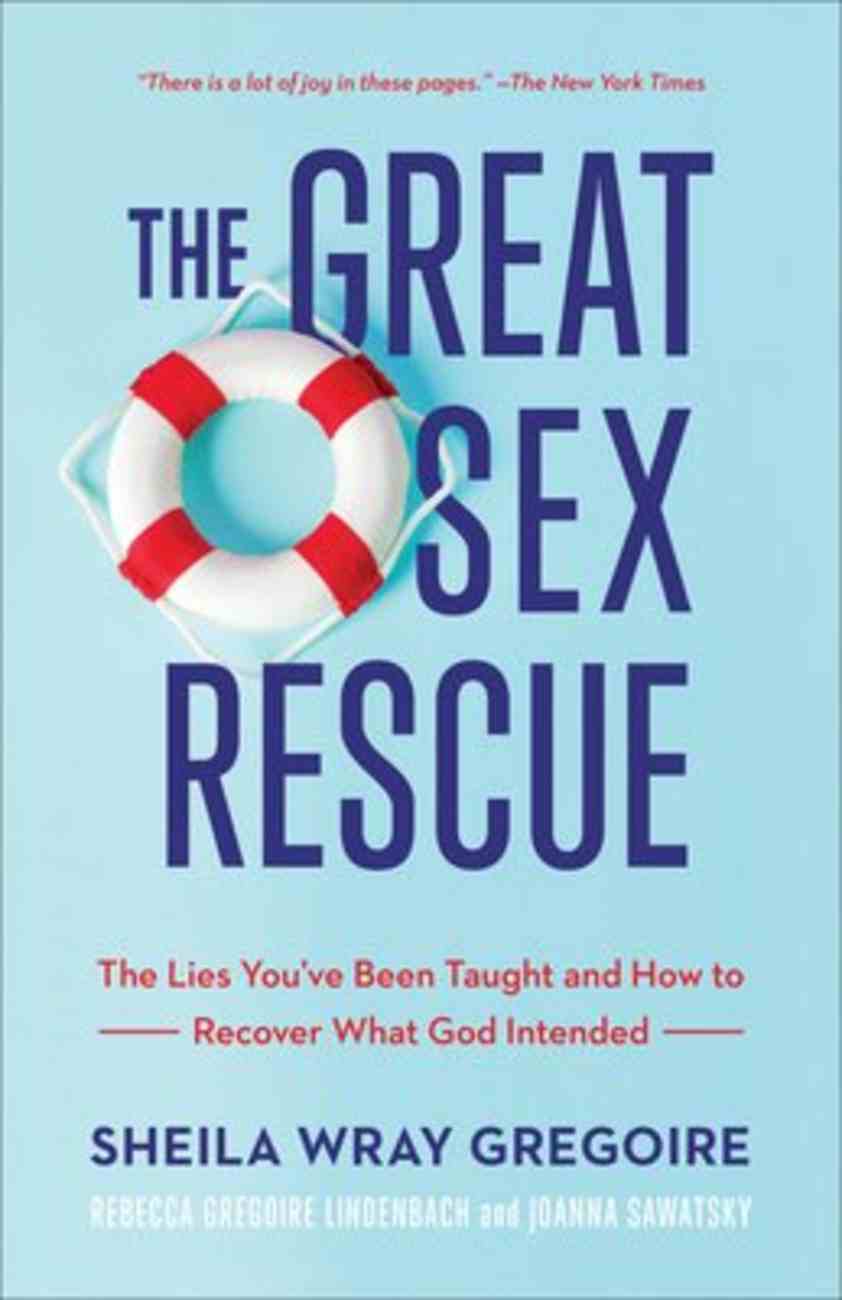

Why the need for whispers? Christians can be weird and awkward about sex at the best of times (often from propriety more than embarrassment).[2] Yet beyond the subject itself, The Great Sex Rescue—as a critique of evangelical teaching on sex—makes for uncomfortable reading and much controversy. Gregoire pulls no punches in the front-page subtitle, The Lies You’ve Been Taught and How to Recover what God Intended.

A Protest Book

The Great Sex Rescue is, at heart, a protest book: “What if our evangelical ‘treatments’ for sex issues make things worse?” (11). It’s a response to perceived flaws in teaching about sex by popular Christian books and arising from the purity culture of nineties American evangelicalism.[3]

The Great Sex Rescue

Sheila Wray Gregoire

What if it’s not your fault that sex is bad in your marriage?

Based on a groundbreaking in-depth survey of 22,000 Christian women, The Great Sex Rescue unlocks the secrets to what makes some marriages red hot while others fizzle out. Generations of women have grown up with messages about sex that make them feel dirty, used, or invisible, while men have been sold such a cheapened version of sex, they don’t know what they’re missing. The Great Sex Rescue hopes to turn all of that around, developing a truly biblical view of sex where mutuality, intimacy, and passion reign.

To show the harmful effects of this teaching, the book analyses the results of a survey of 22,000 women. Alongside this statistical data, it’s the haunting personal stories recounted from focus groups which capture the mess that sinfulness wreaks in intimate relationships.

In place of what is currently taught, Gregoire proposes a positive framework to make the married sexual relationship more equitable—that sex should be personal, pleasurable, pure, prioritised, pressure-free, putting the other first, and passionate. The tone and content of the book, however, is weighted towards critiquing the ways Christians have gone wrong.

Correcting an Imbalance

Gregoire shows that there is much that needs critique. Consider, for example, the bizarre way 1 Corinthians 7:1–5 (perhaps the clearest Bible passage addressing sexual relationships within marriage) is usually taught. Gregoire observes that sex and marriage books use these verses to “spend an inordinate amount of time warning women not to deprive their husbands” (51). It is odd that verses emphasising the mutuality of sex in marriage are applied by some as if they’re written exclusively for wives.[4]

It is odd that verses emphasising the mutuality of sex in marriage are applied by some as if they’re written exclusively for wives.

Gregoire says the teaching that sex is mostly for husbands is the reason the sexual desires of wives are neglected. For,

When evangelical culture frames sexual fulfilment again and again as something he needs and she might get as a bonus, what message are couples going to internalise? Women won’t expect to enjoy sex, and men won’t think anything’s particularly wrong if she doesn’t. (53)

Though it’s easy to discount this assessment if it doesn’t resonate with one’s own experience, the book’s underground popularity suggests it is giving voice to opinions quietly held by many women.

A Female Perspective

By providing a female perspective neglected by other Christian books, The Great Sex Rescue is filled with fresh takes: emotional connection is a need for men not just women (chs. 2–3); sexual technique should be given less importance (ch. 4); men’s and women’s libido differences are better categorised as spontaneous vs responsive rather than high vs low (ch. 7); quality of sex should be prioritised over quantity (chs. 9–10); and the genuinely laugh-out-loud observation that a woman’s period is framed by many books as a difficult time not for the wife but for the husband (206)! The irony is not lost on me—a male reviewing a book that bemoans the church not listening to the experiences of women. However Gregoire directly challenges husbands and pastors (I am both) to reflect on what is being argued.

The Great Sex Rescue also highlights the important issue that experiencing pain during sex is disproportionately high amongst Christian women.[5] “It’s long been known in medical circles that conservative religious women experience more pain with sex than the general population” (57). Gregoire makes a compelling case that this is a result of well-intentioned but misapplied teaching. Biblical warnings against pre-marital intercourse, if taught carelessly, create negative associations about sex. Meanwhile, encouragements to wait until marriage can glorify the wedding night, increasing the chances of an unpleasant first sexual experience. Even the godly desire of wives to serve their husbands can lead to enduring pain during sex rather than speaking up.

Wrong Path, Right Critique

The book does have some shortcomings. Whilst the Bible is quoted throughout, at times the survey results appear to hold more authority than careful exegesis of Scripture.[6] To give one example: the observation is made that a wife should not be blamed for her husband’s use of pornography, with survey results indicating that wives motivated by this fear have decidedly lower sexual satisfaction (85). It is true and biblical to say that a husband’s sexual sin must never be excused and he is responsible for his own ungodliness. Yet the Bible adds an important nuance which couples also need to hear: if you prioritise sex within marriage it has the potential to decrease the temptation to sexual sin for both of you (1 Cor 7:5).

Whilst the Bible is quoted throughout, at times the survey results appear to hold more authority than careful exegesis of Scripture.

One inconsistency in The Great Sex Rescue is its approach to differences between men and women. The case is made—and few would disagree—that men and women have vastly different experiences of sex. This is captured by “the orgasm gap”: 95% of husbands climax most or all of the time during sex compared to 48% of wives (11–12). Is the solution to this disparity found by minimising gender differences or leaning into them?

Gregoire suggests we would benefit from jettisoning traditional gender roles (30) and replacing male leadership and female submission with shared power (32–33).[7] In a book filled with many stories of men abusing power, it is understandable an egalitarian solution is proposed. “Stop talking about rights and hierarchy and power. Let’s put Jesus, who came not to be served but to serve, back at the centre” (242).

At the same time, Gregoire acknowledges there are real and ongoing differences between the sexes. Whilst alert to the danger of gender essentialist attitudes (for example, assuming all men universally desire more sex than all women (125)), she nevertheless notes trends differentiating men and women.

Moreover, many Christian couples (especially amongst Gregoire’s target audience) remain convinced that God designed these biological differences to align with specific gender roles in marriage and church. Rather than dismissing those who hold these views, it would have been fruitful to also demonstrate how male headship modelled on Christ is always self-sacrificing—putting the needs of your wife above yourself. Consequently wives can encourage their husbands to lead in a self-sacrificing way (Eph 5:25–27; 1 Pet 3:7).[8] Even the difference in couples between spontaneous and responsive libidos can support a healthy complementarity that is less dictator (‘he demands then she acquiesces’) and more an intimate dance (‘he initiates with the first step and she responds in kind’).

The biggest limitation, though, is theological: The Great Sex Rescue makes too much of sex. I am thankful the book confronts issues of real pastoral concern but the optimism about redressing these runs the risk of creating new pastoral issues. For example, it is unhelpful to describe orgasm as “the pinnacle of human emotional experience” (217) because it leads to unrealistic expectations for those married and the feeling of missing out for those who are not. Sex is portrayed almost as an end in itself, blessing the couple, but with little vision of any greater good. And this lack of an ultimate purpose for sex then leads to the inclusion of questionable anecdotes, such as those implicitly condoning divorce and remarriage to pursue greater sexual satisfaction (50).[9]

The book also makes too little of indwelling sin. Gregoire is rightly hopeful that struggling couples can improve their marriages, yet the unfortunate reality is that sin and selfishness can lead to ongoing dissatisfaction, including sexual dissatisfaction, even in the best marriages. The sins the book is addressing might have remedies through the practical exercises suggested at the end of each chapter.[10] But the enduring negative effects of sin means we also need to develop spiritual remedies—patterns of repentance and grace.

The enduring negative effects of sin means we also need to develop spiritual remedies—patterns of repentance and grace.

These particular weaknesses—the quality of the book’s biblical exposition, its treatment of differences between the sexes and the degree of theological rigour—are exactly what many evangelicals view as their own strengths and increase the likelihood some readers might discount the book’s message entirely, even though many of its criticisms need to be heard.

Lessons for Leaders

Whether one accepts the broader argument of The Great Sex Rescue, it provides two important lessons for every Christian leader. The first is: recommend books carefully. Many of the quotations from popular Christian books make for uncomfortable reading, especially if, like me, you’ve read or recommended some of these titles without noticing the flaws. I have some concerns over the fairness of assessing older books according to current knowledge, standards and sensitivities but the point remains that if they are no longer helpful they should no longer be recommended.[11]

The second lesson to Christian leaders is: choose your words carefully. We must aim for greater precision in the way we teach about sex to avoid being misunderstood. For example, it’s simply unacceptable that due to our poor communication, Paul’s instruction to not deprive one’s spouse—of either sex (1 Cor 7:5)—is being heard as ‘a wife cannot refuse her husband’s request for sex’ (173).[12] So also, lazy assumptions, such as that sexless marriages are always the result of a wife’s sinful refusal rather than a possible indication of a husband’s sinful neglect, must be abandoned (140). Male pastors need to be mindful of how they will be heard by female congregation members; we would benefit from seeking input from women as we prepare to teach on these topics.

The second lesson to Christian leaders is: choose your words carefully.

Gregoire gives examples at the end of each chapter on how to rephrase potentially misleading teaching. To my ear, most sound clunky, but there is helpful clarity gained if “[instead of emphasising] ‘You do not have authority over your body; your spouse does.’ [You] Say, ‘God wants sex to be a mutual, loving experience’” (178).

Not a Book for Everyone

The Great Sex Rescue is not a book for everyone. The analysis of misguided teaching about sex requires a directness that could be TMI (‘too much information’) for some. Reading this book may also not be the best way to prepare Christian couples to begin their married life. If an engaged couple has not been shaped by the harmful teaching Gregoire highlights then why introduce it at length? On the other hand, its insights and correctives should certainly inform pre-marital counselling. The book’s popularity in Australia suggests Gregoire has identified experiences amongst Christian women that are far more common than we realise.[13] In general, though, the less detailed expectations newlyweds have—whether good or bad—the better for working it out together. Some of the best advice from the book for the about-to-be-married is: don’t place too much pressure on the wedding night itself.[14]

But for anyone who has been influenced by the ideas this book critiques, for those a few years into marriage or those seeking to troubleshoot problems there is much food for thought. Husbands and wives can benefit from external voices as they navigate sensitive topics. And if, as this research suggests, many Christian couples have unresolved sexual issues, then reading a book such as The Great Sex Rescue could be the catalyst for a much-needed conversation.

After the Placards and the Pitchforks

The Great Sex Rescue stirred up controversy upon its release (not least for the way its book rating system neuters so many popular titles) and Gregoire, for her part, often amplifies these controversies on social media. Anyone aware of this discourse or those who feel defensive when their favourite evangelical authors are slighted can easily dismiss a protest-book like The Great Sex Rescue altogether.[15]

Yet we need to remember how protests work. When I visualise political protests the two objects which come to mind are placards and pitchforks—both of which make sharp points: placards wound by words (with a tendency to memorable overstatement) and pitchforks prod the opponent (provoking strong reactions). This is the challenge for evangelicals goaded by Gregoire’s protests about Christian teaching on sex: can we get past the sharpness of the message to discern its legitimacy?

You won’t agree with everything you read. But you don’t need to either. Because another thing about protesters is they don’t always make for the best government. In some ways it’s easier to destroy than to build. The most valuable role played by the protestor isn’t providing the perfect solution but highlighting the problem. If Christian leaders are humble enough to listen to Gregoire’s critique, revisit the ways we talk about sex and reassess the books we recommend, then we may find that a lot less Christian sex will need rescuing.

[1] The book is co-authored with Rebecca Gregoire Lindenback, who contributes anecdotal content, and Joanna Sawatsky who provided statistical analysis.

[2] In light of recent TGC controversies I welcome awkwardness over inappropriateness.

[3] Some books from this era include: E. Elliot, Passion and Purity: Learning to Bring Your Love Life Under Christ’s Control (1984); M. Peace, The Excellent Wife: A Biblical Perspective (1995); J. Harris, I Kissed Dating Goodbye (1997); S. Omartian, The Power of a Praying Wife (1997); D. Gresh, And the Bridge Wore White: Seven Secrets to Sexual Purity (1999); S. Arterburn, Every Man’s Battle: Winning the War on Sexual Temptation One Victory at a Time (2000); E. Eggerichs, Love & Respect: The Love She Most Desires; The Respect He Desperately Needs (2004).

[4] 1 Corinthians 7 is referenced throughout the book, describing how wives are told their husband will be unfaithful if they don’t have enough sex. Thus, “Women can feel as if they’re having sex with a metaphorical gun to their marriage” (90).

[5] The common forms of pain listed are dyspareunia, vulvodynia and vaginismus (57).

[6] There are a few egregious proof-texts. For example, “Chapter 9: ‘Duty sex’ isn’t sexy” begins with a quotation of Matthew 10:8, “Freely you have received; freely give.”

[7] In fairness, I agree with much of what the authors have to say regarding unilateral decision-making by a husband being bad practice for a unified relationship (and contravening the ‘mutual consent’ commanded in 1 Cor 7:5).

[8] It is disappointing to see the cynical approach to all forms of complementarianism, including dismissing one author’s instruction that husbands defer to their wife’s preferences. Gregoire is critical of this advice, saying it is given in hope ‘his wife forgets her opinions don’t have as much weight’ (33).

[9] Considering the author’s criticism of the careless examples found in other books, I was surprised to read unwise anecdotes, such as one about visiting a topless beach (84), or a wife wondering out loud if her sexual pain would be lessened if she’d given in to teenage passion instead of waiting for marriage (62–63).

[10] Each chapter concludes with an, “Explore Together” section of practical advice. There is potential danger in giving overly prescriptive advice because it can create pressure if either spouse is unwilling or uncomfortable to follow what is suggested. I haven’t read Gregoire’s other works but my current recommendation to couples for a positive treatment of the topic is The Best Sex for Life by Dr Patricia Weerakoon.

[11] The criticism of other authors is forceful and direct but there is occasional graciousness in acknowledging, “The authors who perpetuated this mentality simply did not write their books with abused women in mind. Their aim was to increase the frequency of marital intercourse, and they didn’t consider their effect on women in abusive situations” (185). The intensity feels a bit odd from the perspective of Australia, which didn’t seem to have the same degree of opposition to sex education in schools and thankfully avoided most of the odder fringe of purity culture, such as purity rings and dad-daughter commitment ceremonies.

[12] Christians have a tendency to address the issue of sexless marriage by directing wives to 1 Corinthians 7:5 rather than husbands to Ephesians 5:28 or 1 Peter 3:7.

[13] I occasionally hear pastors commending Christian marriage because Christian couples have comparatively more frequent sex than unbelievers. It is worth pondering if sexual frequency is a better metric than sexual satisfaction because I suspect husbands equate the two in a way many wives do not.

[14] Instead wait until you’re married and both of you are turned on—which realistically may not occur on your wedding night at the end of one of the most exhausting days of your life.

[15] Tim and Kathy Keller’s The Meaning of Marriage, for example, is ranked as neither ‘Harmful’, nor ‘Helpful’, but is ‘Neutral’ by Gregoire’s criteria.