There’s so much of the short history of Australian Christianity yet to be told—especially in a way is accessible to the average Christian. One exciting part of this history is the enormous amount of ‘home mission’ evangelistic work in the nineteenth century, as churches scrambled to catch up with the exploding European population spreading out across the continent and concentrating in a few cities that transformed from tiny settlements to bustling towns to modern cities of hundreds of thousands of people in a matter of decades. One of the giants of this period was surely John MacNeil (1854–1896).

Zeal

John was born in Scotland, moved to Australia but returned to Scotland for theological study. Even while studying theology, this suffered because of his involvement in evangelistic work in the slums of Edinburgh. John’s letters and diaries, quoted at length in his widow Hannah’s biography, are full of burning zeal, earnest prayer, desire to know God more deeply and be more useful in the cause of the gospel.

John was an intense, rugged and hardworking evangelist, often travelling enormous distances on horseback or bicycle in remote areas to preach the gospel, whether as a minister in regional South Australia, evangelist in the very wild west of the mining towns of Western Australia—where he and Hannah spent their honeymoon in 1884 (!?!) and to which he returned in 1894, or itinerant evangelist back and forth across all the Australian colonies and even over the Tasman Sea.

Eccentricity

MacNeil was that kind of evangelist which seems to pop up in every generation: someone who ruffles feathers and pushes boundaries. His biography contains many fond, harsh and perplexed criticisms of his manner; and just as many apologies, concessions and defences of him. “He had a free and easy manner that scandalised those who were more conventional,” Hannah explains. She tells of regular encouragement from friends and critics for him to guard his words and conduct, to be “more circumspect in future”. But

it was no use trying to pin up Vesuvius, and friends began to realise that he would be himself in spite of them all, and that it must be left to time and to the mellowing influence of the Holy Spirit; to soften down what he himself called ‘excrescences’.

She also quotes from one of his letters where John reported that people would talk of him as a “madman” or “a bit of a wizard”… but that the Lord used this to bring more people to come and hear him speak.[1]

Itinerant Evangelism, Church Renewal and Church Planting

John’s ministry life had a pattern to it: brief periods of church ministry followed by longer periods of itinerant ministry. He was at Jamestown in South Australia for eighteen months, during which time both the church and surrounding home mission stations were renewed (1879–1881). Then, as a result of a period of spiritual crisis, he returned to Victoria, where his family had first migrated when he was five years old, to work as an evangelist, initially employed by the General Assembly of Victoria (1881–3) and then freelance but still endorsed by the Assembly (1883–1885). After reaching a point of debilitating sickness and exhaustion he moved to Sydney, to help start a church in Waverly (1885–8). Then he was employed as the ‘Assembly Evangelist’ by the Presbyterian Church of Victoria (1891–5) and then worked freelance again in 1896.[2]

It says something about John’s gargantuan capacity for ministry work that he took a rest by planting a church! And the church he planted in Waverly was a humming ministry centre. His slogan was “A church is not a field to work in, but a force to work with.” Hannah describes the programs established during John’s time as minister in Waverly:

- a prayer meeting at 7am on Sunday,

- young men’s and young women’s fellowship meetings at 9:45am,

- the morning church service at 11am,

- a 2:30pm teachers’ prayer meeting,

- 2:45pm Sabbath school or special children’s service,

- 4pm prayer for teachers and senior scholars,

- 6:30pm congregational prayer meeting before the evening service, church workers going out to invite people to attend the evening service,

- 7pm evening service,

- an after-meeting following the evening service which would finish around 9pm;

- during the week a ladies meeting was run by John’s wife Hannah on Tuesday afternoons,

- the MacNeils hosted an open ‘evening at home’ where they would receive visitors,

- a Wednesday evening service (“a kind of Bible reading”) and

- a weekly open-air meeting conducted by the Young Men’s Association.[3]

As the call of wider evangelistic work began to pull on John’s heart once more, the church tried to keep him a little longer: they hired an assistant minister and set him free for six months of the year. But even this only kept him for another eighteen months.

Freelance Evangelist and Assembly Evangelist

John had briefly been employed as an evangelist by the General Assembly of Victoria in the early 1880s, and this position was renewed, with more financial backing from 1891 to 1895.[4] His evangelistic work was of a revivalistic sort, but influenced by the significant Scottish Calvinist revivalistic heritage and so spared some of the worst excesses of what is often associated with revivalism.[5]

Pre-Millennialism, Second Blessing and Miraculous Healing

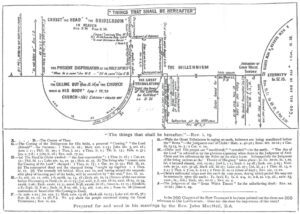

A peculiar feature of late-nineteenth century evangelicalism is how much interest there was in end-times prophecies and pre-millennialism. Many were also seeking and commending an empowering experience of Spirit-Baptism or higher life; and expected physical healing in answer to the right kind of prayer and faith. John’s spiritual life was marked by all these things. The spiritual crisis mentioned above led to him experiencing what he considered a second blessing of the Spirit; a debilitating dyspepsia, which contributed to his retirement from itinerant work in 1884, was soon to troubled him no more, which he attributed to ‘the prayer of faith’; and he even wrote his own end-times charts:

Pentecostalism, when it really emerged with the Azusa Street Revival in 1906, didn’t come out of nowhere. There were proto-Pentecostal ideas and movements already at work.

On the one hand, these beliefs certainly added further fuel to John’s intensity and frenetic evangelistic activity—although his God-given temperament was definitely just as significant a factor. On the other hand, these beliefs also added a degree of turmoil to his spiritual life, which a spirituality more deeply shaped by his fundamental Presbyterian theological convictions might have freed him from.

Death

John died suddenly of an aneuryism while on mission in Queensland. He was about the same age I am now. The closing section of Hannah’s biography is a tear-jerker. She describes longing for his return, hearing of his death, and then receiving several warm and joyful letters he had posted prior to his death, looking forward to his homecoming arriving one after another.

The biography Hannah wrote soon after John’s death is available for free online on Trove, and is possibly in a library near you. It is well worth a read!

Further Reading

His widow, Hannah, wrote a biography of him, with a large amount of excerpts from his letters and diaries and other primary sources. It’s a great read and you can find it on Trove.

Australian Church historian Darrell Paproth also wrote a chapter on him in the now out of print Presbyterian Leaders of the Nineteenth Century.

Tasmanian Church historian Elisabeth Wilson also talks about MacNeil among others in her PhD Thesis on nineteenth-century British Evangelists in Australia.

His book The Spirit-Filled Life is available on Project Gutenberg.

[1] MacNeil, John MacNeil: Late Evangelist in Australia and Author of ‘The Spirit-Filled Life’, a Memoir by His Wife, 88, 114, 119–20.

[2] He started his final period in Victoria as minister in the working class Melbourne suburb of Abbotsford (1889–91).

[3] MacNeil, John MacNeil, 168, 172–73, 176–78.

[4] This set a precedent for future evangelists to be employed in the decades up to the First World War: William Fraser, A. Allan, John Fairley and L. C. M. Donaldson (Donaldson was specifically a ‘young people’s evangelist’).

[5] Remember, ‘Revivalism’ isn’t a dirty word!