Eighteen years ago, I sat with my husband, Geoff, in the back of a little, blue taxi, Ethiopian pop music blaring, winding our way through the backstreets of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Driving through the gates into the compound of the Kidane Mehret Children’s home, we held hands and trembled. We made small talk with two elderly Italian nuns (Sister Camilla, tall, smiling, and gracious; and Sister Ludgata, dumpy, dour, and sharp) until Gebriael Geoffrey Edwin Keith was carried into the room.[1] He was beautiful, bald as a billiard ball, and ours. Minutes later, we were driving back out of the gate (still trembling) with our precious baby, clutched in my arms.

The parent–child relationship is a familiar biblical picture of God’s relationship with his people (for eg Is 43:1–7 and 1 Jn 3:1), so it may surprise you that the idea of an explicitly adoptive relationship between God and his people is rare. The Greek word translated as ‘adopted’ or ‘adoption’ (huiothesia) appears in Scripture only a handful of times to describe the change in the status of believers because of their salvation. So says Paul in Galatians 4:1–7 that Christians are no longer slaves but God’s kids.[2]

In the twenty-first century, the idea of adoption is, in most people’s minds, primarily about the nurturing parent–child relationship. In our world, adoption is a permanent, legally binding, family-forming event. In contrast, adoption in the ancient world was primarily about inheritance rather than creating an environment to raise a child. In fact, it was frequently an adult receiving sonship through adoption, becoming the heir of his or (rarely) her new father.[3] Michael Horton notes that spiritual adoption is also both legal and relational.[4] Legal sonship changes our relationship with God. We are his heirs, but we are also included in deep, loving relationship. Reflecting on my lived experience as an adoptive mum has focused my understanding of this relationship in three ways:

Adoption Love Is Deep

The day we met Geb was absolutely a case of parental ‘love at first sight’. There is a sense, though, in which our love for him was of an earlier date. The process to adopt was long and arduous, invasive, and expensive. We waited… and waited… and waited. Throughout the whole process we had a deep sense of connection to our hoped-for child. We prayed for them, we talked about them, we bought things for them, we longed for them. Our joy the day we got “the call” was indescribable. Our love for this little boy we had never seen was bone-deep and visceral. I have had people tell me that they don’t know if they could love a baby they didn’t give birth to. I never felt that way. My adoption love for Geb was so fierce and deep that during my pregnancy with his brother, Roscoe (our biological child), I was convinced that there was no way I could love the baby I carried as much as I loved Geb. But I do!

But God’s adoption love for us is so much greater than my love for Geb. My adoption love looked forward to welcoming a cute helpless baby, capable of giving love, as well as receiving it. God’s adoption love welcomes us when we were slaves to our sin. Spiritually speaking, our sin made us ugly, filthy, diseased, and feral. We were God’s enemies. At best, we decided that we were fine on our own and we could save ourselves, thanks very much. At worst, we were militantly anti-God, spewing blasphemy and desiring nothing more than to kick him in the shins and run in the opposite direction. My adoption love caused us to put aside our privacy and pour out our time and money. God’s adoption love was willing to pay a far higher cost to bring us into his family: the blood of his son, Jesus (Rom 5:6–11).

Adoption Is Transformative

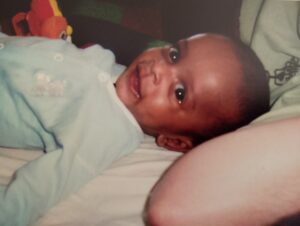

Gebriael was eight months old when we met him, but he didn’t look it. Many months in an institutional setting had left him severely malnourished, ill with multiple infections and delayed in developmental milestones.[5] He was frail, floppy, and blank-eyed; the doctor we visited said he probably would not have survived another week (a thought that still makes my blood run cold and leads me to thank God for his perfect timing). But our adoption of Geb was transformative.

Some changes happened almost immediately—within a day, he was making eye contact, giggling, and putting his feet in his mouth. He gained a kilo in the first week and his infections began to clear. By the time we got home to Tasmania he was babbling and holding up his head. Other transformations happened more slowly. It was a year before he took his first steps. His teeth were damaged by prenatal malnutrition, so we had to be vigilant with dental care. Today, the baby who nearly didn’t make it is a strong, intelligent, handsome eighteen-year-old; a born sportsman, a talented musician, and a whizz with younger children (and he has excellent teeth!).

If Geb’s transformation after his adoption was profound, ours, as God’s children, is nothing short of miraculous. We weren’t in need of food, medicine, and the love of parents, we were completely and utterly dead. In adopting us, God made us alive. He didn’t just patch up our broken, sinful hearts, he gave us new ones, capable of loving him. He didn’t just give us physical food, he gave the spiritual food of his Word to make us grow and continues to renew our minds. Through adoption, God transforms us from the inside into children who have the family resemblance: he makes us grow up to look like Jesus (Rom 8:29).

Adoption Does Not Erase the Past

If you passed Geb in the street today, or spent time chatting to him, you might not realise he had a difficult start to life. But the reality is that Geb’s early traumatic experiences, and those of his birth-mum during her pregnancy, have affected him irrevocably. Psychologists have long recognised that negative experiences, even those that happen before we can remember, change our psychology, brain chemistry, and emotions. The emerging study of epigenetics is showing us that the effects of trauma are not just “in our minds” but in our bodies too; our environment changes, sometime irreversibly, the way our genes work. In the years since we adopted Geb, our love for him has led us to try and give him everything he needs emotionally, spiritually, and physically. But, as our adoption worker told us early in our adoption journey, love isn’t enough. The marks of trauma remain and always will.

In this life, it is the same for us as Christians. We have been adopted by God, with all the benefits that brings, but we live with broken, sin-soaked hearts, minds, and bodies in a broken, sin-soaked world. We can’t escape our sin—it’s as if it is in our DNA, passed on and on and on since Adam and Eve first disobeyed. It has been this way for every person who has ever lived—except one. Jesus, our sinless older brother, was born into poverty and scandal. He was misunderstood, abused, rejected, accused of madness and drunkenness, assaulted, abandoned by his closest friends, falsely accused, and tortured. As he died on the cross, he took on our sin and the brokenness of the world and in his humanity was separated from his heavenly Father. But Jesus is both the perfect man and the divine Son of God. He isn’t shaped by his environment; the universe is subject to him. So instead of being indelibly marked by the trauma, pollution, or condemnation of sin, Jesus defeated it once and for all. In the now, our spiritual adoption is incomplete. We are children of God, but our sin and the sin of others still marks us. Jesus’ resurrection points us to the ‘not yet’ of our adoption: the hope of a day when our sin and the sin of others, and the effects of both, will be erased entirely (Rom 8:23–25). There will be no more sin and death, and all our tears will be gone (Rev 21:4). We will be beloved, adopted children, finally in our forever home.

Geb, if you’re reading this (and I hope you are), being your mum is one of the biggest privileges of my life. I’m so thankful for you. But I’m also thankful that there is a Father who loves you more than I ever could, wants to transform you to be like Jesus, and offers you an eternal home with him. I pray every day that you will follow him. Love you!

[1] In Ethiopia, as in many places in the world, your surname is your father’s name. Ideally, you have at least two generations reflected in your name. Geb bears the names of his dad, paternal grandfather and maternal great-grandfather, as well as our family surname.

[2] The adoption metaphor has an interesting in Galatians, where we are told that in one sense, a child (whether adopted or not) doesn’t gain the full benefits of sonship until they reach a majority: “he is no different from a slave, although he owns the whole estate” (4:1). The work of Christ and the giving of the Spirit brings about the fullness of our “adoption to sonship”—both for Jews and Gentiles (4:4–7).

[3] Lindsay, H. Adoption in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

[4] Horton, M. The Christian Faith: A systematic theology for pilgrims on the way. Grand Rapids:Zondervan, 2011, 645.

[5] I want to pay tribute to the Kidane Mehret Children’s Home and places like it around the world which serve, love, protect and care for children, often with little support and no recognition. I thank God for them. Gebriael’s condition was not because of simple neglect, mismanagement, or lack of love. It was a result of few resources and great need in a world that is so very, very broken. Please pray for and give to organisations like this. And please pray, ‘Come, Lord Jesus!’