Part 1: The Shape of the Canon

The Big Picture of the Bible (Genesis 1 and Revelation 21–22)

The beginning and end of a literary work often tells you a lot about the core message of the work. Even though the collection of books which make up the canon of Scripture as we have it today was put together much later than when they were written, the beginning and the end of the final shape of the canon have much to tell us about the nature of God and his focus in dealing with his world. These in turn are indicative of how we should read the Scriptures as a whole.

Genesis 1

Whatever else we can say about Genesis 1, its primary purpose is to tell us about God. Among the multiple perspectives about him, two key theological ideas emerge. The first is that he is the Creator. The second is that he is purposeful in his creation. This latter notion is captured at the end of the sixth day when we are told that…

‘And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day.’ [Genesis 1:31]

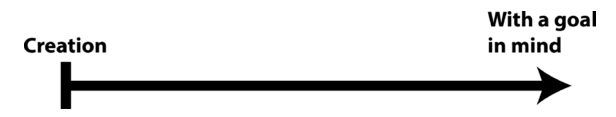

The Hebrew word for ‘good’ that is used here has a very broad range of meanings, such as ‘pleasant’, ‘practical’, ‘suitable’, ‘nice’, ‘friendly’, ‘just’, or ‘morally good’. However, some have argued persuasively that the sense here is functional, that is, ‘appropriateness’.[1] In other words, the creation is good in the sense that it is an appropriate or suitable place where God can work towards his goal for his creation.[2] God as the Creator creates the world with a good goal or end in mind. We could represent this using the following diagram.

As we read on in Genesis 2 and 3 we find that in some sense God’s good intentions for his creation are corrupted by human independence and rebellion. The result is that at the end of Genesis 3 we find that although God had an ideal in chapter 1 that involved humans, that ideal is not fulfilled or is waiting for fulfilment. The sign of this is that God shuts humans out of his presence (Genesis 3:22–25) and we find ourselves waiting and hoping for God’s ideal to be met.

Revelation 21–22

If we move now to the final two chapters of the Bible we find a different picture. There is now a great city that is described as having echoes of the garden heard about in Genesis 1–3. For example, we are told about the tree of life from which humans were barred in Genesis 3 but which is now accessible.

These verses paint a picture of the end of God’s purposes. That end is one in which there is no curse. Instead, in the place of curse there is healing and salvation and continued access to God. Sin is banished and God’s blessing is perpetually poured out by God on his people.

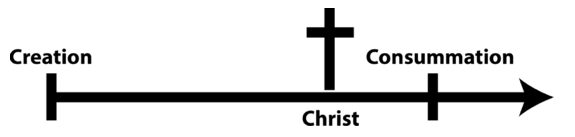

We know this Lamb from Revelation 5 … Jesus Christ, who was slaughtered but also raised from the dead, is the key to God’s purpose.

However, there is also a very new critical new element about the garden—the presence of the Lamb (Revelation 21:22). We know this Lamb from Revelation 5 where he is the focus of attention in answer to the search for the one who is worthy to unlock the scrolls, that is, God’s plans for history. There the Lamb stands before the throne of God as one slain but who remains standing. The point of the imagery appears to be that the Lamb, Jesus Christ, who was slaughtered but also raised from the dead, is the key to God’s purposes and the one who stands at their centre.

This brief overview of the way in which the Bible begins and ends lets us into the mind of God and informs us that

- God is a God of purpose or ‘end’.

- This end involves the created world, humanity, and God.

- This end will be realised and will be realised in history. After all, the world is a suitable and appropriate and good place for God’s end to be realised.

- God’s end for his world finds its focus, centre, and end in Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ is the centre of God’s plan for the ages; the centre of history; the goal and end of God’s purposes in history.

In the light of Rev 21-22, our previous diagram might now be redrawn to look like this:

Implications

The implications for reading the Bible are that…

- We should read the Bible realising that it tells a story that has a God planned trajectory. It is ‘going somewhere’ and is therefore teleological in focus.

- The ‘somewhere’ to which the story of the Bible is travelling finds its centre and guarantee in Christ (cf. Ephesians 1:9–10).

The impact for reading the Bible is that when we do, we should read it in the light of God’s purpose in Christ. Sometimes this purpose will be blatantly evident in a single verse. At other times, this purpose will be more complicated and might only be evident as a whole book is viewed within the Bible in its entirety. Nevertheless, the Bible as a whole is saturated with God’s purpose in Christ.

In this short article we have tried to get a big perspective on the task of understanding the Bible as Christian preachers and readers. In the next part, we will begin an examination of some key New Testament texts that might guide us in the details of how we might approach proclaiming the Old Testament as Christians.

For the rest of this series, see Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

[1] Claus Westermann, Genesis 1-11: A Commentary, transl. John J. Scullion (London: SPCK, 1984), 166.

[2] Perhaps in the same sense that a fisherman might build a boat, look upon it, and then pronounce it ‘good’, that is, good/appropriate for the purpose for which he built it—to catch fish.