To read God of the Garden is to take a stroll through a forest. There is a lot of meandering; there are paths that suddenly lead down into hidden valleys or up to ridge-line vistas; there are tiny things to peer down at in fascination and giants to look up at in awe. And sometimes, it can be a little bit tricky to see the wood for the trees.

There is a wood there, however—or rather a whole lot of woods. Andrew Peterson’s God of the Garden is a meditation on the wonders of the natural world, and a celebration of the God who made that world. Along the way, it is also a reflection on Peterson’s own life: his childhood and his fall from innocence; his mental struggles as an adult with a successful career in music; his raising of a family; and his love of things made and grown by hand.

A Romantic Work

On one level, God of the Garden is a romantic work. It laments the unstoppable march of suburbs and the deadening influence of a society built on money and individualism. It extolls the rolling hills of the English countryside with their publicly accessible footpaths. It looks back through the generations of the Peterson family and reflects on the years of the writer’s own life. It also idealises the lost world of childhood:

From a distance of forty years, I see that little boy climbing into the maple boughs to look at the [bird’s] eggs, and I want to hug him. Even now, my heart swells a little, and I clench my jaw to keep from crying for the sadness of what was lost, and lost so soon. Pain was sure to come, but I didn’t know it yet … The summer days gleamed with blue and green and gold, the nights with fireflies, the winters with moonlit snow. The two maples framed the backyard and offered their shade in June, their glory in October, their stark outlines in February, their russet buds in April. (8)

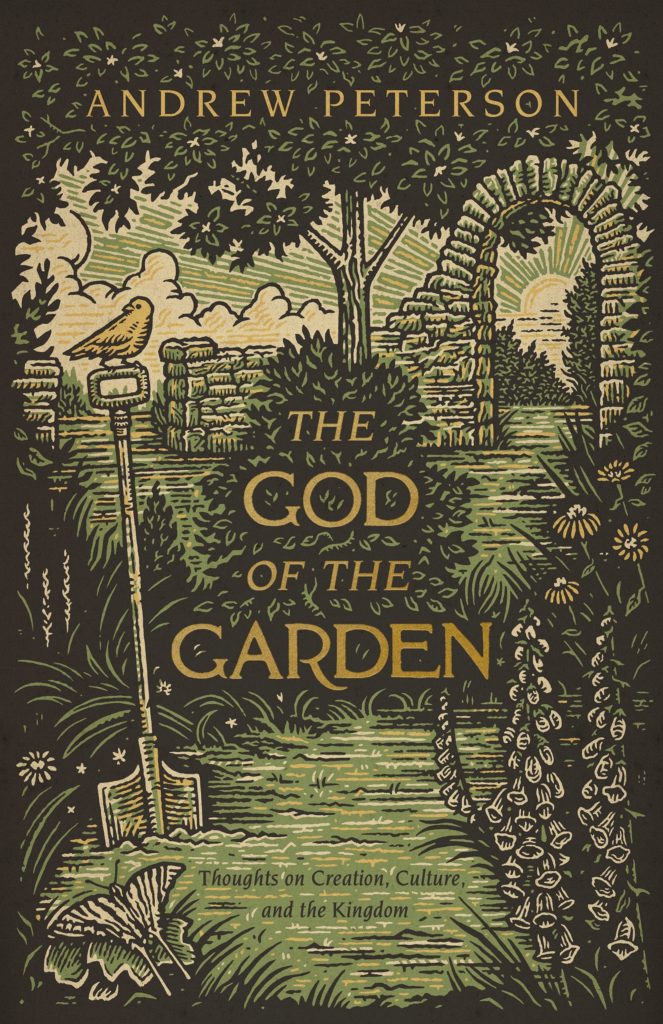

The God of the Garden: Thoughts on Creation, Culture, and the Kingdom

Andrew Peterson

The God of the Garden: Thoughts on Creation, Culture, and the Kingdom

Andrew Peterson

There’s a strong biblical connection between people and trees. They both come from dirt. They’re both told to bear fruit. We talk about family trees, passing along our seed, cutting someone off like a branch, being rooted to a place, or bearing the fruit of the Spirit. It’s hard to deny that trees mean something, theologically speaking.

This book is in many ways a memoir, but it’s also an attempt to wake up the reader to the glory of God shining through his creation.

J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis would, of course, approve of this—as would Wordsworth, whom Peterson quotes throughout. But Peterson is not just here to wax nostalgic (though he certainly does that); he wants to celebrate the ongoing grace of a still-beautiful creation—especially its trees. God of the Garden is full of appreciative reflections on maples, live oaks, bristle-pines, and olive trees. Trees, in their beauty, grandeur, longevity—and also in their tragic destruction—stand both for themselves and as symbols of a good world gone wrong:

Oh, how I longed for Eden. How I grieved the razing of this gloried creation in exchange for the perfunctory development of featureless subdivisions. How I longed for those immaculate fields of corn, those bright, breeze-blown maples under the Illinois sky. I longed for a garden of old trees and a silence that spoke of God’s good pleasure in the world he made. I thought of the wide, sunlit prairies of my childhood in Illinois, followed by my adolescence in the dark shade of the stormy Florida wild, of shadows that had multiplied in my heart there like a nest of roaches, and wanted desperately to reclaim some vision of what had been lost. Could I give my children a better memory? Could that boon to their story help to redeem my own? (64)

There is a lot of this kind of thing, and readers less inclined to wear their hearts on their sleeves (like this one) might find it a bit too much. But Peterson’s grief over sin and its effects on creation is undoubtedly a healthy response. It echoes the frustration of creation: “groaning together in the pains of childbirth” until “the revealing of the sons of God.” (c.f. Rom 8:18-25)

The Comfort of Creation

His recourse to the created world as a balm for this grief is proper too. Heaven and earth are full of God’s glory (Ps 19:1; Is 6:3)—powerful testimonies to grace and wonder that we neglect at our peril. Charles Spurgeon himself warns closeted ministers to get out into the open air:

He who forgets the humming of the bees among the heather, the cooing of the wood-pigeons in the forest, the song of birds in the woods, the rippling of rills among the rushes, and the sighing of the wind among the pines, needs not wonder if his heart forgets to sing and his soul grows heavy. A day’s breathing of fresh air upon the hills, or a few hours’ ramble in the beech woods’ umbrageous calm, would sweep the cobwebs out of the brain of scores of our toiling ministers who are now but half alive.[1]

Andrew Peterson offers a similar testimony. He bears witness to the lifesaving benefits he has received from simply being outside and tending his garden through the seasons:

I’m no master gardener, not by a long shot, but it’s hard to imagine life without it now. In the early spring I can almost hear the garden calling me outside to pull weeds or deadhead flowers, to gasp at some new bloom that’s opened up in quiet glory. After being indoors for hours at a time working on a story or a song, the sun on my face and the nearness of growing things rejuvenates me like nothing else. (117)

In the early spring I can almost hear the garden calling me outside to pull weeds or deadhead flowers, to gasp at some new bloom that’s opened up in quiet glory

Like the true convert, Peterson presses his cure on the rest of us. He offers intriguing scientific evidence that working in the soil benefits us physiologically and mentally (I am listening to Julia Baird’s Phosphorescence as I write this, and it is interesting to note the similarities here). Urging us to live lives that are closer to nature, he tells us to pursue “a graceful integration of nature and culture;” to move at “human” pace rather than “automobile speed”.

The Potential Pitfalls

There are two potential traps for a book like God of the Garden. One danger is stopping short of the cross—drawing forth good and true common-grace reflections from the world yet failing to point us toward the glorious interruption of nature brought by Jesus in his life, death, and resurrection.

The other danger is to stop at romanticism: to make this world our heaven or overstate the significance of the created world and its grace. This is the trap Lewis cautions us against in his seminal essay “Weight of Glory”:

The [things] in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them … If Wordsworth had gone back to those moments in the past, he would not have found the thing itself, but only the reminder of it; what he remembered would turn out to be itself a remembering. The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them; it only came through them.

The [things] in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them

Avoiding the Pitfalls

Andrew Peterson, to his credit, works to steer wide of these hazards. He reserves his most passionate descriptions for those times and ways that the world of leaf and flower has pointed him back to the grace of Christ: a winter forest that made him think of Gethsemane; a trip to the Mount of Olives that refreshed his perception of Christ’s work on the cross. He writes,

The Blessing drank to the dregs the cup of the Curse … He entered our death that we might enter his resurrection. In his agony, ours finds meaning and redemption; our pain is subsumed in the tidal wave of Christ’s, and washes up clean on the shores of Glory. It was under the olive boughs of Gethsemane that Jesus’ gaze at last rested on the frightened little boy. (183)

He also reminds us that this current world is not for keeping and the true garden is still to come. I will finish with one of the passages I found most moving, as Peterson reflects on the beauty, tragedy, and hope of gardening in the context of his parent’s retirement property (named “Shiloh”):

Our loves are handed down quietly. With each visit to Shiloh I’m confronted with two realities: the Garden and the Fall. Shiloh, to me, is the best of what can happen when humans root themselves to a place. Not only does the place grow better, the humans do, too. …

But the knowledge that the memories that drape the limbs like Spanish moss will be lost to time, forgotten like native songs, overgrown with weeds or wrecked by the wilful ignorance of progress, fills me with a terrible grief. What will become of my mother’s gardens? … What will become of my father’s woodshop, where with a pipe between his teeth, he happily turns candlesticks on the lathe? … The great sadness of Time will bulldoze it beyond recollection.

And here is where faith strides into the scene, clothed with vitality, to remind us of the hope it plants and the love it grows. I have faith that there is a resurrection coming, and our present sufferings are nothing to the glory that will be revealed in us. … Glory be to God, Time itself will be redeemed, because it will no longer be an adversary, but a friend, an everlasting Sabbath, an unending feast. If my mom and dad made Shiloh new in thirty years, think what they’ll do with a million. (51)

[1]Charles Haddon Spurgeon, Lectures To My Students