I recently discovered that Chile has legislated for a public holiday on October 31, the day we celebrate as Reformation Day, remembering Luther’s posting of the 95 Theses on the door of the Castle Church in 1517. But when I ask people what the 95 Theses taught, silence is frequently the answer. The text itself is relatively unknown. By contrast, the words spoken by Luther on this day, April 18, 500 years ago, when he appeared before the Emperor, Charles V, at his Diet in Worms, are remembered and celebrated, providing us with both an image of protest and words of explanation which summarise his resistance: “Here I stand.” In some ways, it is a more potent picture of Protestantism, representing Luther with more assured theology leading to more decisive outcomes. The tension begun in 1517 is finally resolved by 1521.

From Wittenberg to Worms

Recall first of all, that Luther posted his 95 Theses to debate the place of penance and indulgences in the life of the late medieval church. It was not the Mass that was under his microscope. Whether he had come to understand justification by faith in a new way before this time is something scholars still argue about. It does not shape very much the argument in these theses. But his doctrine of grace was certainly being reconsidered at this time.

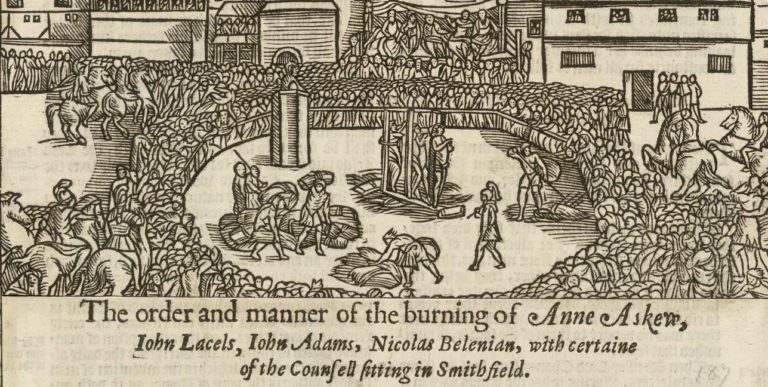

Then in the course of 1518 and 1519, Luther attended several significant theological meetings to defend his new insights concerning the grace of God. In Heidelberg, he debated with the Augustinian brothers and grew in clarity concerning faith alone. In Augsburg, he met the papal legate, Cajetan, and clarified his view of the nature of authority in the church. In Leipzig, he confronted his fellow German, Eck, and defended his view of Scripture alone, siding with the so-called heretic Jan Hus of Prague, who a hundred years earlier had shaken the cage by arguing for church services and preaching in the vernacular, along with other doctrinal and administrative reforms in the church. His growing clarity around these core convictions was only now leading him to a concrete agenda.

In December of 1520, Luther burnt a copy of the canon law and the Pope’s bull declaring him a heretic—perhaps, literally, the most incendiary moment of the movement for reform yet.

The year 1520 saw the publication of the three treatises, through which Luther’s reforming ideas are chiefly known: The Appeal to the Christian Nobility, The Babylonian Captivity, and The Freedom of a Christian. Each in its own way, pushed his agenda further, arguing that freedom from papal absolutism, freedom from the captivity of the seven Catholic sacraments, and freedom from justification by works of the law defined his demands for a purified church. In the December of 1520, Luther walked down the main street of Wittenberg to a site just outside the town walls, where hospital rags had once been burned. And there he burnt a copy of the canon law and the Pope’s bull declaring him a heretic—perhaps, literally, the most incendiary moment of the movement for reform yet. But more was to come.

Though Luther now stood officially outside the church, he maintained the trust and protection of his local prince, Frederick the Wise of Saxony—a powerful man who, as one of seven imperial Electors, had just presented the boy Charles V with his crown. After Frederick had successfully lobbied the new Emperor to give Luther another chance to recant, the reformer was called to answer for his radical views before the Emperor himself. Luther cherished the opportunity to make his progress from Wittenberg to Worms, gathering crowds in each town he passed through, like a martyr to the cause. This was to be not just a legal climax to his church trials but was also a theological climax to years of reflection, in which he had tested his views through acerbic debate with enemies and scholarly dialogue with friends.

Courtroom Drama

On the first day of the proceedings, in both Latin and German, Luther was asked to identify his writings and to recant his views, to sing the old song of traditional Catholic faith. Expecting a debate and not just a few perfunctory questions, Luther wanted to move the trial from a legal proceeding to one in which theology was discussed, for this was a sure hand that he had successfully played before. He in turn asked for the interrogation to adjourn to further consider his position until the next day. It is of course clear that Luther had been pondering these issues from any number of angles for some years. The Emperor, hoping to have kowtowed him into submission with his grandeur, granted Luther’s request.

Luther turned the table on his inquisitors when they resumed on April 18.

In a dramatic display not of surrender but defiance, Luther turned the table on his inquisitors when they resumed on April 18. He was the grand master of bold flourishes. He first asked to be shown exactly which of his writings he should recant, given that he had written on many different theological topics. Surely he wasn’t being asked to recant his teaching on the creeds or to renounce theological opinions that had not been condemned in the papal bull? He did allow that he might have spoken too boldly on some issues, and he was prepared to accept responsibility for those breaches. But on the major order of the day, he refused to change his mind, but instead announced:

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. I cannot do otherwise, here I stand, may God help me, Amen.”

Luther thereby confessed that the overall significance of his prophetic ministry was to call the church back from reliance on external forms to a commitment to the reforming authority of the Word of God. He stood before the Emperor to point out the grievous errors of the church and refused to budge on the importance of the Scriptures to stand over the church in judgement. Recognising the role of reason, he nonetheless was not captive to it. Recognising the role of conscience, he yet remained bound by it. Recognising the authority of the Emperor, he had nonetheless grown increasingly confident in his role as reformer.

The Real Turning Point

Interestingly, in the original Latin text of the proceedings, the final sentence here is in German. Some have suggested therefore that it was not original, and that Luther only later uttered the words “Here I stand.” Either way, this was a turning point of more consequence than anything in Luther’s career to date, for the Emperor would now declare him an outlaw as well as heretic. He could neither count on protection from the church, nor from the Empire. Quoting Psalm 27, Luther was later to reflect that though all should forsake him, the Lord would not. He turned quickly towards Wittenberg, only to be kidnapped on the way home by Frederick’s soldiers—another twist in the tale of the Lord preserving his spokesman.

As he stands before medieval rulers, argues that the church is a creature of the Word (and not the other way around) and entrusts himself to the Lord’s providential care, Luther gives us great reasons for contending that today is the best occasion to mark the Reformation. Anyone stand with me?