Allow me to melt your brain. In 1836 Melbourne looked like the picture above: a tiny rural town (pop. 177). Within fifty years it was one of the great modern world cities! How much did evangelism have to change between, say 1836 and 1902? How much might it need to change between 1902 and 2024?

The late-nineteenth-century evangelists like Reuben Torrey (lead evangelist for the 1902 Melbourne Simultaneous Mission) pioneered a means of reaching these emerging cosmopolitan industrial cities like Melbourne and Chicago. Such a mission field required more coordination than American frontier revivalism, or the pre-Industrial-Revolution cities and towns of the Evangelical Revival, for example. The simultaneous mission approach coordinated the churches of a city in a vast network of prayer meetings, satellite suburban mission events and centralised inner-city mass rallies, with an aim to saturate the whole modern city with the gospel.

The 1902 Simultaneous Mission was heavily promoted through the mass media of the Christian and secular press, through doorknocking and fliering. They were supported by increasingly sophisticated approaches to ‘personal work’: where ministers and non-ordained volunteers sought to follow up individuals who attended the mission events for personalised evangelistic and pastoral care.

These incredible efforts did have a positive impact on the spread of the gospel, the health of churches, the engagement of youth and the raising up of leaders. But even with all the prayer and preaching, early-twentieth-century evangelicals struggled to keeping up with population growth.

Familiar New Methods

The kind of mission practices that were used in the 1902 Melbourne Simultaneous Mission were not novel for Australian church leaders at the time. Not only were revivals in Britain and America widely publicised, there had been local revival meetings in Australia, including prior simultaneous missions. For example in the same year as the Melbourne Mission, another was taking place in the Illawarra region, and the Presbyterian Church of Victoria had organised a simultaneous mission in 1901.

In 1888–89 the General Assembly appointed John MacNeil as Church Evangelist. He conducted many missions across Victoria and further afield until his death in 1896. MacNeil was an instrumental founder of the Evangelisation Society of Victoria and the Prayer Band that was central to plans that led the 1902 Mission. Sadly, he died suddenly at the age of forty-one, before he was able to see the climactic outcome of his work.

A Population Open to Being Evangelised by Christians

Not only was the simultaneous mission approach to evangelism suited to the particular challenges of the emerging modern city, it was also suited to a significantly Christianised population. Stuart Piggin and Robert Linder observe:

Such [large] attendances are evidence that evangelistic rallies, where the Gospel was preached and conversions sought, were a staple part of the culture. They were copiously reported in the Press. Australians expected to be evangelised and whether or not they had experienced and professed conversion was a matter of some concern to a sizeable proportion of the Australian population.[1]

Mass Evangelism and Twenty-First Century Australia

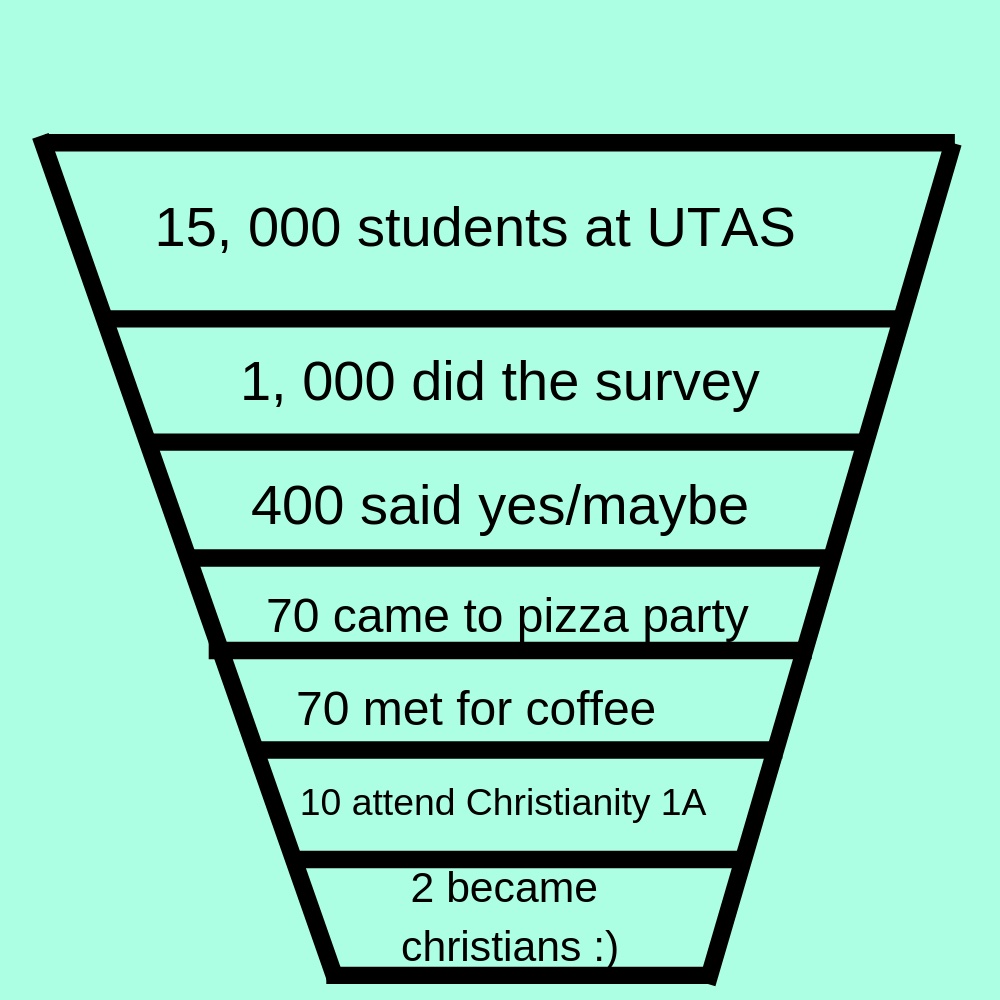

My perception is that by and large Christian leaders realise that such events are less central to fruitful evangelistic efforts in our day—they play an occasional, supplementary role to the steady, ongoing work of evangelism; they serve as possible feeders for the more effective evangelistic work that happens when some of those who attend the rally then sign up for the ongoing evangelistic course (see the flowchart we’ve used in the past to explain our Christian Union’s O Week Missions). In the last century, ongoing ‘personal work’ has grown in its evangelistic significance, far outweighing the mass rally in missiological value.

A concern of this series of articles about revivalism has been to encourage us to be self-aware about patterns, practices, values and expectations that we take for granted as Christians: recognising that some of these are inherited evangelical traditions, rather than immovable theological necessities.

Much of our attitudes to evangelism, it seems to me, is still shaped around models of ministry pioneered in the Victorian and Edwardian eras: when evangelicals were first figuring out how to reach this new phenomenon of the industrialised city.[2] Our culture has changed a lot since then; our cities have changed a lot since then—Melbourne is ten times the size it was in 1902. Communication and transportation technology are vastly different; as are religious beliefs, moral norms, and family patterns; as are our migration patterns and so our ethnic demographics. As a result, it is perfectly reasonable that what it means to be a zealous evangelist will also manifest differently in 2024.

What does that adjustment mean in practice? It means rejoicing in the stories of a different age, but not giving them too much mythological power. It might mean not assuming that walk-up evangelism or open-air preaching is the most pure form of evangelism; it might mean not seeing the enormous citywide rally as the most triumphant evangelical achievement; it might mean recognising that a Zoom prayer meeting may be a legitimate model for corporate prayer rather than insisting on in-person, mid-week, mass prayer meetings.

While we might pray that some of the features of earlier periods would re-emerge, we can also eagerly look forward to different ways in which the Holy Spirit uses preaching, prayer, the godly life and godly community to save many souls and revive the church in our day.

Sections of this article were adapted from my article “Strategies for Church Relations During the 1902 Melbourne Simultaneous Mission”, Lucas 2.20 (December 2022) 87-116.

[1] Stuart Piggin and Robert Dean Linder, The Fountain of Public Prosperity: Evangelical Christians in Australian History 1740-1914 (Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2019), 436.

[2] These methods were refined and mastered as the twentieth century wore on (albeit disrupted by two world wars) reaching an apex in the mid-century Billy Graham crusades.