Next time you visit the Melbourne CBD, walk a few blocks north of the city to the majestic Carlton Gardens and look at the vast Royal Exhibition Hall, built for the eighth World’s Fair in 1880 (pictured above). Now imagine this Hall filled with 6 000 people for a whole week for daily evangelistic meetings. Imagine people flocking through the parks to enter the building, and spilling out afterwards into the Melbourne night. It’s a thrilling thought.

200 Churches, 100 000 Prayers, 50 Preachers, 8 000 Conversions

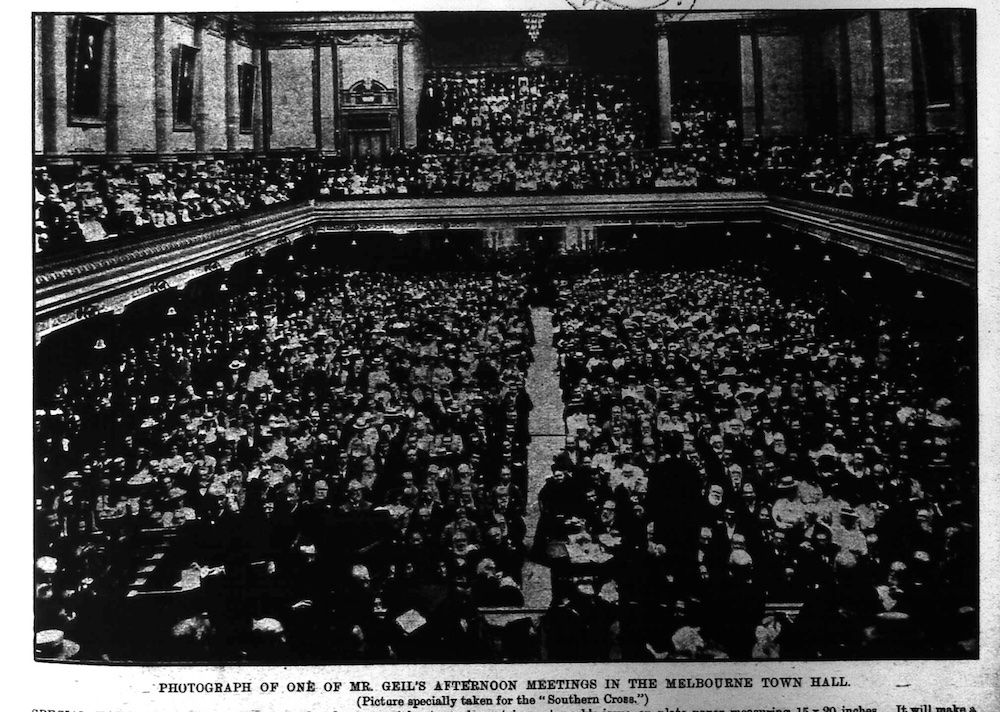

The Melbourne Simultaneous Mission was an enormous organisational undertaking that resulted in huge attendance numbers across Melbourne in April 1902. Instigated by the Evangelisation Society of Victoria, the Mission was organised by a committee of seventy, with seven hundred engaged in local sub-committees[1] and drew in 214 churches, along with a large number of parachurch organisations.[2] In addition to the massive city-centre events at the Town Hall and Exhibition Building in its second week, it also included fifty mission sites across Melbourne and used fifty local ‘missioners’ along with the international speakers Rev. Dr. Reuben A. Torrey (together with accompanying singer Charles Alexander), William Edgar Geil and Rev. D. C. Davidson.[3] Over 117,000 participated in prayer meetings in the six weeks prior to the Mission,[4] over 250,000 attended the Mission events themselves (about half of Melbourne’s population at the time)[5] and 8,624 made a profession of faith.[6]

The First Global Evangelist?

Just before its commencement, The Southern Cross declared that

The Mission, in a word, represents the most serious, energetic, and comprehensive plan yet undertaken for the evangelisation of the city.[7]

Historian Stuart Piggin describes the Mission as “probably the greatest evangelistic campaign in Australia’s history prior to the 1959 Billy Graham crusade.”[8] Historian Geoffrey Treloar argues that in the larger journey of which this Mission was a central part Torrey was the first to fully exploit

the possibilities of international revivalism by going around the world preaching the gospel in a single, sustained evangelistic campaign conducted along modern lines.[9]

It is surprising how little known this mission is among Australian evangelicals today.

Across a few articles I am going to offer some reflections on this enormous evangelistic effort.

The Need for Faithful Pragmatism

The Simultaneous Mission was alternately described as both a mission and a revival. As I’ve argued in an earlier article, revivalism isn’t a bad thing. The question is whether our revivalism practice is godly and biblical, or unrestrained and manipulative.

When we plan for evangelism and conversions; spiritual maturity and renewal; or zeal for evangelism and world mission, we are engaging in revivalistic efforts, in a sense—especially if we are praying and planning for a significant increase in gospel fruit. Intensely emotional preaching, singing and praying is not the only form of revivalism. We may work towards revival through sound preaching and theological conferences; setting apart educated and properly accountable evangelists; cooperating through sensibly governed parachurch networks; implementing basic strategic planning; and conducting orderly prayer meetings.

A common observation in the Christian media reporting on the Melbourne Simultaneous Mission of 1902 was how reasonable, measured and controlled the events were: they were not given to disorder and excess. Careful planning is not necessarily more or less revivalism than organic and spontaneous prayer and evangelism.

Better than telling ourselves that we aren’t revivalists, I think, is to seek to be godly and faithful revivalists. We too, could fall into some kinds of unchecked pragmatism, if we are not careful; it’s just that our pragmatism might look different to another kind which we more easily dismiss as ‘crass revivalism’. One clue that we are falling into unhealthy pragmatism is that we put too much emphasis on specific methods, often methods which were pivotal in the last season of revival, as necessary to effective ministry. Particular kinds of meetings or modes of prayer or conferences or evangelistic techniques can subtly become imbued with too much spiritual significance.

To use the example of the 2024 Meet Jesus campaign, here in Australia, it is unlikely that the phrase or branding itself will be invested with too much power. But is it possible that, for example, ‘Uncover John’ could? Uncover John is a merely a brand, some merchandise and a collection of methodologies. There is nothing magical in this particular edition of John’s Gospel. Nor a special recipe in a list of ‘five Rs’ to reading John’s Gospel. In fact, personal evangelism need not involve reading any of the four Gospels: I came to faith through ‘Scripture Under Scrutiny’ studies based around Romans 1–5 and reading books by C. S. Lewis.

As with any works of human effort, our contributions to ministry and mission can easily become a source of pride and fixation, if we don’t watch ourselves. And over time, this can puff up. In 1909 and again in 1912 Alexander returned to Melbourne with American Presbyterian evangelist Wilbur Chapman, for similar mission efforts, although of diminishing scale. It is interesting to note that these subsequent attempts at simultaneous missions were marked by more organisation, more international speakers (and their entourages), more advertising and merchandising (the sale of hymn books and souvenir publications, full-page advertisements and multi-page inserts in the Southern Cross newspaper)… and yet smaller numbers of attendance and conversion. Our bold and zealous efforts for the cause of Christ can so easily start to spill over into hubris and over-emphasis on human effort.

Failure brings one set of temptations in ministry and mission, success another; passive fatalism is one grave failing for the Christ’s church, human-centred pragmatism another. It’s not that we avoid revivalism for fear of its excesses, rather, we proceed with faith and prayer, in fear and trembling, with regular pauses for reflection, assessment and adjustment.

Much of this article is adapted from my article “Strategies for Church Relations During the 1902 Melbourne Simultaneous Mission”, Lucas 2.20 (December 2022) 87-116.

[1] Reports on this detail are ambiguous, seeming to imply 700 committees, which is unlikely.

[2] ‘The Week’, The Southern Cross, 18 April 1902, XXI.16 edition, 423, National Archives of Australia, State Library of Victoria.

[3] ‘The Simultaneous Mission’, The Southern Cross, 4 April 1902, XXI.14 edition, National Archives of Australia, State Library of Victoria. Although generally now known as the ‘Torrey/Alexander Revival’, the actual prominence of Geil in the promotion and city-centre meetings mean it would more accurately be called the ‘Torrey/Alexander and Geil Revival’.

[4] ‘The Week’, 18 April 1902, 423. Dr W. Warren reports the number as “over forty thousand”. (W. Warren, ‘The Genesis of the Australian Revival’, Mission Review of the World 25, no. 3 (March 1903): 202.). The discrepancy is best explained by understanding the higher number to be the estimated number of unique visitors across the entire six weeks.

[5] Stuart Piggin, Spirit, Word and World: Evangelical Christianity in Australia (East Brunswick: Rainbow Book Agencies, 2012), 59.

[6] Reuben A. Torrey, The Power of Prayer and the Prayer of Power, 1924 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1971). Cited in Piggin, Spirit, Word and World, 26.

[7] ‘The Week’, The Southern Cross, 28 March 1902, XXI.13 edition, National Archives of Australia, State Library of Victoria.

[8] Piggin, Spirit, Word and World, 59. Stuart Piggin and Robert Linder also say that “Australia came close to a national awakening in 1902”. Stuart Piggin and Robert Dean Linder, The Fountain of Public Prosperity: Evangelical Christians in Australian History 1740-1914 (Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2019), 531.

[9] Geoffrey R. Treloar, ‘The First Global Revivalist? Reuben Archer Torrey and the 1902 Evangelistic Campaign in Australia’, Church History, 2021, 7. He writes: “it did inaugurate one of the most intense, sustained and geographically distributed periods of revival and revivalism in the history of Protestantism”. Treloar, ‘The First Global Revivalist’, 25. Treloar also observes how the Mission was a major turning point in Torrey’s career, and yet, it is rarely written about in historical works, including those concerning Torrey’s life. Treloar, ‘The First Global Revivalist?’, 2. Torrey and Alexander’s global tour made an impression around the globe—even earning them a passing mention in James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses. James Joyce, Ulysses, Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1992), 190.