John Stott visited Australia in January 1965, and this visit, one of many, had a profound effect on Australian preaching.[1] Stott gave Bible studies on 2 Corinthians at the Anglican Church Missionary Society Summer Schools in several states in Australia. Much Australian preaching at that time was on ‘a text’, that is, on an individual verse from the Bible, often without much regard to its context. In his Bible studies John Stott was demonstrating the obvious value of preaching from passages of Scripture, and from consecutive passages of Scripture. His example had a profound impact on Australian preaching, initially transforming preaching in Anglican churches, but soon also in other churches as well.[2]

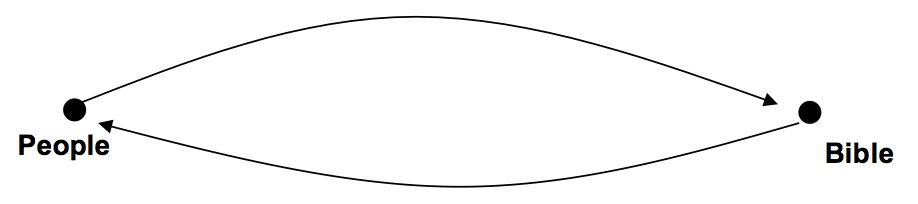

Preaching is not exposition only but communication, not just the exegesis of a text but the conveying of a God-given message to living people who need to hear it.

Stott’s ministry of preaching and teaching included Sunday-by-Sunday sermons at All Soul’s Langham Place, London, where he served as Rector from 1950-75,[3] as well as speaking at university missions, missionary conferences, and Bible conventions around the world; his many Bible commentaries and other books; and his work in training preachers in many countries, continued today by Langham Preaching.

Reviving Systematic Expository Preaching

Under God, he was part of a revival of systematic expository preaching in the UK in the 20th Century, which was achieved through Willie Still in Aberdeen, and Martin Lloyd-Jones, John Stott and Dick Lucas in London, and has spread around the world.

What lessons can we learn today from his writing on preaching?

In his 1982 book, I believe in Preaching,[4] he reminds us that ‘Preaching is indispensable to Christianity’ (p. 15). He defends the monologue sermon, but explains that, though it is a monologue in style, it should be a dialogue in purpose and content.

One of the greatest gifts a preacher needs is such a sensitive understanding of people and their problems that he can anticipate their reactions to each part of his sermon and respond to them. (p. 61)

This includes an awareness of their initial response to the reading of the Bible passage, as well as the preacher’s exposition of the passage. It depends on the preacher knowing people, as well as knowing the Bible; and loving people, as well as loving the Bible. He develops this idea in Chapter Four, Preaching as Bridge-building. (pp. 135-179)[5]

We have to help people to travel to the world of the Bible, to ponder its message, enter its culture and world, and receive it in its own context. Then we have to show them how to bring that message back to their own lives, to this contemporary world. In Stott’s words,

… this is because preaching is not exposition only but communication, not just the exegesis of a text but the conveying of a God-given message to living people who need to hear it. (p. 137)

We naturally do this when we are explaining and applying the Bible to individuals, and are often prompted to do so when they ask us how they should put it into practice! We need to provide the same connections, build the same bridges in our sermons. Our sermons need to be and to sound authentically Biblical, and authentically 21st Century, authentically historical and authentically contemporary.

This is both necessary and possible because of three theological convictions which underly preaching: ‘Scripture is God’s Word written (p. 96); ‘God still speaks through what he has spoken’ (p. 100); and ‘God’s Word is powerful.’ (p. 103)

Stott also writes of the relationship between the Bible and the church:

… the Church is the creation of God by his Word … Not only has he brought it into being by his Word, but he maintains and sustains it, directs and sanctifies it, reforms and renews it through the same Word. (p. 109).

A deaf church is a dead church: that is the unalterable principle. God quickens, feeds, inspires and guides his people by his Word (p. 113).

Bible reading is the one time in the week in which God addresses his people as a congregation, as a unit, as a body.

One of the significant features of the Bible is that it mostly addresses the people of God, not individuals. The prophets mostly address the people of God in their corporate life, and most of the New Testament letters are addressed to churches. And even when individuals are addressed, there is an implied message to God’s people. This should challenge us to use the Bible for the audience for which God caused it to be written, namely, God’s people. Our tradition of applying its message to individuals is legitimate, but only if our primary application is to the corporate life, values, attitudes, strengths, sins, and weaknesses of our churches.

What is the significance of the Bible reading and sermon in our services? It is the one time in the week in which God addresses his people as a congregation, as a unit, as a body. If God spoke these words in the past to his people, we should use them for the same purpose today. See the New Testament letters as examples of how to do this, and see also Christ’s message to the seven churches in Revelation chapters 2 and 3.[6]

One more insight from this book. Stott quotes Samuel Vodeba: ‘the written word of God is pastoral through and through in its message, spirit and purpose.’ (p. 120) We often think of the word ‘pastoral’ as referring to the care of individuals. But ministers have to pastor the flock even more than they have to pastor individuals—members of the church may pastor each other: the minister has the primary responsibility for pastoring the church. We should not only think of preaching as teaching, but also as pastoring—and this should shape our style of preaching, and our attitude in preaching. Am I demonstrating love, understanding and compassion, as well as truth and clarity?

Stott and Simeon

Stott also wrote an introduction to a collection of sermons by Charles Simeon, the minister and preacher at Holy Trinity Cambridge for 54 years, from 1782-1836. Simeon was an outstanding preacher in the university and town of Cambridge, an evangelical strategist, a student of preaching, and an encourager and trainer of 1000 preachers.[7] He was one of Stott’s heroes.

Here are some of Simeon’s insights, according to Stott.

Simeon was willing to suffer for what he believed and preached. (p. xxx)—For more than ten years Simeon suffered strong opposition from the church of which he was minister, from the town, and from the university, even though many came to hear his sermons. He patiently endured insults, bad behaviour, and obstructions to his ministry. However, he endured and persisted, made the most of his opportunities, and won the day.

He kept on learning how to preach, and so not only learnt how to preach better, but was also better able to train others to preach. He was a life-long student of Scripture. (pp. xxxv-viii)

Simeon was committed to preaching what was in the Bible, and not using it for his own purposes:

My endeavour is to bring out of Scripture what is there, and not to thrust in what I think may be there … never to speak more or less than I believe to be the mind of the Spirit in the passage I am expounding. (p. xxxiii)

He did not let a theological system, such as Calvinism or Arminianism, constrain his interpretation of the Bible or his preaching:

When I come to a text which speaks of election, I delight myself in the doctrine of election. When the apostles exhort me to repentance and obedience, and indicate my freedom of choice and action, I give myself up to that side of the question. (p. xxxv)

He aimed for simplicity and clarity in his preaching

He aimed for simplicity and clarity in his preaching: ‘unity in his subject, perspicuity in his arrangement, and simplicity in his diction.’ (p. xxxvii) His sermons had one theme from the Bible passage, they were coherent in content, shaped to enable understanding, and he used short sentences, and words which all could understand.

He was passionate in his preaching, and not only applied his sermons, but exhorted and entreated people to respond in faith and obedience. (p. xxxviii)

His aim was,

… to carry his congregation as it were to heaven; to weep over them, pray for them, deliver the truth with a weeping, praying heart. [8]

I think that we would improve our preaching if we learnt these lessons from John Stott and Charles Simeon.[9]

Expounding the Word

Let me conclude with two quotations from Stott’s chapter on “Expounding the Word,” in his book, The Contemporary Preacher.[10]

The first is his definition of preaching:

To preach is to open up the inspired text with such faithfulness and sensitivity that God’s voice is heard and God’s people obey him. [11]

With customary clarity he explained that this sentence contained six implications:

- Two convictions about the biblical text: that the Bible text is inspired and that the preacher’s task is to open or explain it.

- Two obligations in expounding it: that we must be faithful to the text and sensitive to our hearers.

- Two expectations: that God will be heard, and that his people will respond. [12]

The second is his statement on the privilege of the preacher.

It is an enormous privilege to be a biblical expositor, that is, to stand in the pulpit with God’s Word in our hands and minds, God’s Spirit in our hearts, and God’s people before our eyes, waiting expectantly for God’s voice to be heard and obeyed. [13]

[1] See Timothy Dudley-Smith, John Stott: A Global Ministry, Leicester, IVP, 2001, 114-16. This includes an account of this visit, but does not comment on the effects on preaching in Australia.

[2] I have used Jonathan Holt’s chapter on ‘The emergence of expository preaching in Sydney Anglican churches’ [online]. St Mark’s Review, No. 230, Nov2014: [72]-83.

[3] He also served at All Soul’s as Curate from 1945-50, and then Rector Emeritus from 1975 until his death in 2011.

[4] John R W Stott, I believe in Preaching, London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1982.

[5] The following diagram is mine, not his.

[6] I should explain that these two paragraphs are my response to Stott’s words as quoted, not an expansion of his ideas in his book.

[7] James Houston, Evangelical Preaching, Portland, Multnomah Press, 1986. Stott’s Introduction is on pp. xxvii-xli.

[8] Simeon’s words, as quoted in J. I. Packer, “Expository Preaching: Charles Simeon and Ourselves.” In Preach the Word: Essays on Expository Preaching in Honor of R. Kent Hughes. Edited by Leland Ryken and Todd Wilson, 140-156. Wheaton, Crossway, 2007, 151.

[9] Simeon provides useful insights for preachers, however he preached from individual texts [verses], and did not engage in systematic expositions of books of the Bible. See, Packer, ‘Expository Preaching’, 148.

[10] John Stott, The Contemporary Christian, Leicester, IVP, 1992, 207-218.

[11] Ibid, 208.

[12] Ibid, 208-18.

[13] Ibid, 218.