I was grateful to God to have come across many excellent books and book recommendations this year. Here, more or less in order, are my top ten.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

This was my favourite novel this year. As I said in my review, it was the perfect lockdown book—being itself about grace, innocence and transformation in the context of malice and enforced isolation. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Truth on Fire by Adam Ramsey

Adam Ramsey shows us how theology ought to be done in this heart-and-head hymn.

Adam Ramsey shows us how theology ought to be done in this heart-and-head hymn to the God who is transcendent and immanent; one and three. Here’s an example of the sort of thing you will find in this exhortation to wonder and rejoice:

Goodness flows out of God as naturally as breath flows out of us. When he speaks, a creation that is “good” is what results (see Genesis 1). The morning sun rises, bursting the night’s darkness with colour and light and the goodness of God. The aroma of freshly-brewed coffee, the gift of taste buds, the emotional outlet of singing, and the existence of laughter—they all point back to a God whose creative goodness included these in the human experience. He did not have to. But his goodness spills over with unrestrained abundance, filling every corner of creation. Because goodness is what God is, goodness is what God naturally does. (p87)

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders

This is simply the best book on writing (at least fiction writing, but maybe all writing) that I have ever read.

Adapting material from his Master of Fine Arts course at Syracuse University, Saunders presents seven short stories from the Russian masters and proceeds to talk about how they work, why they work—and sometimes, why they don’t work as well as they might. Saunders’ compassionate humanity shines through again and again in these essays, along with his many insights into what literature might do for us:

By the end of the story … I feel about Olenka [from Chekhov’s “The Darling”] the way I think God might. I know so much about her. Nothing has been hidden from me. It’s rare, in the real world, that I get to know someone so completely. I’ve known her in so many modes: a happy young newlywed and a lonely old lady; a rosy, beloved darling and an overlooked, neglected piece of furniture, nearly a local joke; a nurturing wife and an overbearing false mother. And look at that: the more I know about her, the less inclined I feel to pass a too-harsh or premature judgment. Some essential mercy in me has been switched on.

For a longer representative sample, see Saunders’ discussion with Ezra Klein.

The Gulag Archipelago by Alexander Solzhenitsyn

A remarkable book and an achievable undertaking (for us slow readers) if you consume it as an audio book and as a single volume. See more here.

Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind by Tom Holland

I was late to the party with this one. Having heard a lot of interviews and read a lot of short form information I assumed I had the gist. But the scope of Holland’s project—to show the overwhelmingly positive impact of Christianity on western history and the western mind—is bigger (and more nuanced) than I realised. Overall Holland has a great thesis, even if we don’t agree with him at every turn: Christianity is everywhere. Even the culture wars of late western society can be viewed as a struggle between different principles of the same Christian heritage:

The idea the great battles in America’s culture war are being fought between Christians and those who have emancipated themselves from Christianity? This is a conceit that both sides have an interest in promoting. It is, though, no less of a myth for that. In reality, conservative Christians and progressives are both recognizably bred of the same matrix.

Opponents of abortion stand in a clear line of descent from Macrina, who toured the rubbish tips of Cappadocia looking for abandoned infants to rescue. And those who argue against them are likewise drawing on a deeply-rooted Christian supposition: that every woman’s body is her own, and to be respected as such by every man. (p530)

Reformed Dogmatics v2: God & Creation by Herman Bavinck

The best reformed theology has always been conversant with other traditions and ideas.

The best reformed theology has always been conversant with other traditions and ideas and Bavinck exemplifies that awareness in this survey of theology proper (i.e. the nature of God and his relation to the world). Without turning from the authority of Scripture, Bavinck acquaints his reader with discussions from East and West, patristic and scholastic theology, pagan and liberal religion. He was a stupendous intellect and remains a great resource for today. Although I thought he was mistaken on a few points, I especially appreciated his recognition of the trinitarian roots of creation (a theme once universally acknowledged but now neglected):

… Augustine teaches us, the self-communication that takes place within the divine being is archetypal for God’s work in creation. Scripture repeatedly points to the close connection between the Son and Spirit on the one hand, and the creation on the other. The names Father, Son (Word, Wisdom), and Spirit most certainly denote immanent relationships, but they are also mirrored in the interpersonal relations present in the works of God ad extra. All things come from the Father; the “ideas” of all existent things are present in the Son; the first principles of all life are in the Spirit. Generation and procession in the divine being are the immanent acts of God, which make possible the outward works of creation and revelation.

Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford

In his first novel, celebrated essayist (and sometimes Christian apologist) Francis Spufford seems to justify the works of God by imagining a parallel universe where five working-class children killed in a (historical) V2 demolition of a London Woolworths go on to live the lives they might have had. Most interesting for this reader was his treatment of Christian conversion—given the difficulty of making it plausible to a general audience these days. Spufford slips past the watchful dragons by making his Christians unfamiliar—both weird and non-WEIRD. Here, from the final page [spoiler!], is his depiction of a believer’s death:

It is morning. It is night. It is morning.

“Ben?’”says Marsha, holding his left hand, “Grandpa Ben?’”says Ruthie, holding his right hand …

Praise him in all the postcodes, thinks Ben. Praise him on the commuter trains: praise him upon the drum and bass. Praise him at the Ritz: praise him in the piss-stained doorways. Praise him in nail bars: praise him with beard oil. Praise him in toddler groups: praise him at food banks. Praise him in the parks and playgrounds: praise him down in the Tube station at midnight. … Praise him in trouble. Praise him in joy. Let everything that has breath, give praise.

The sun is overhead. The sun is shining straight down. The grass grows bright with ordinary light. Ben sees the light, and the light is very good.

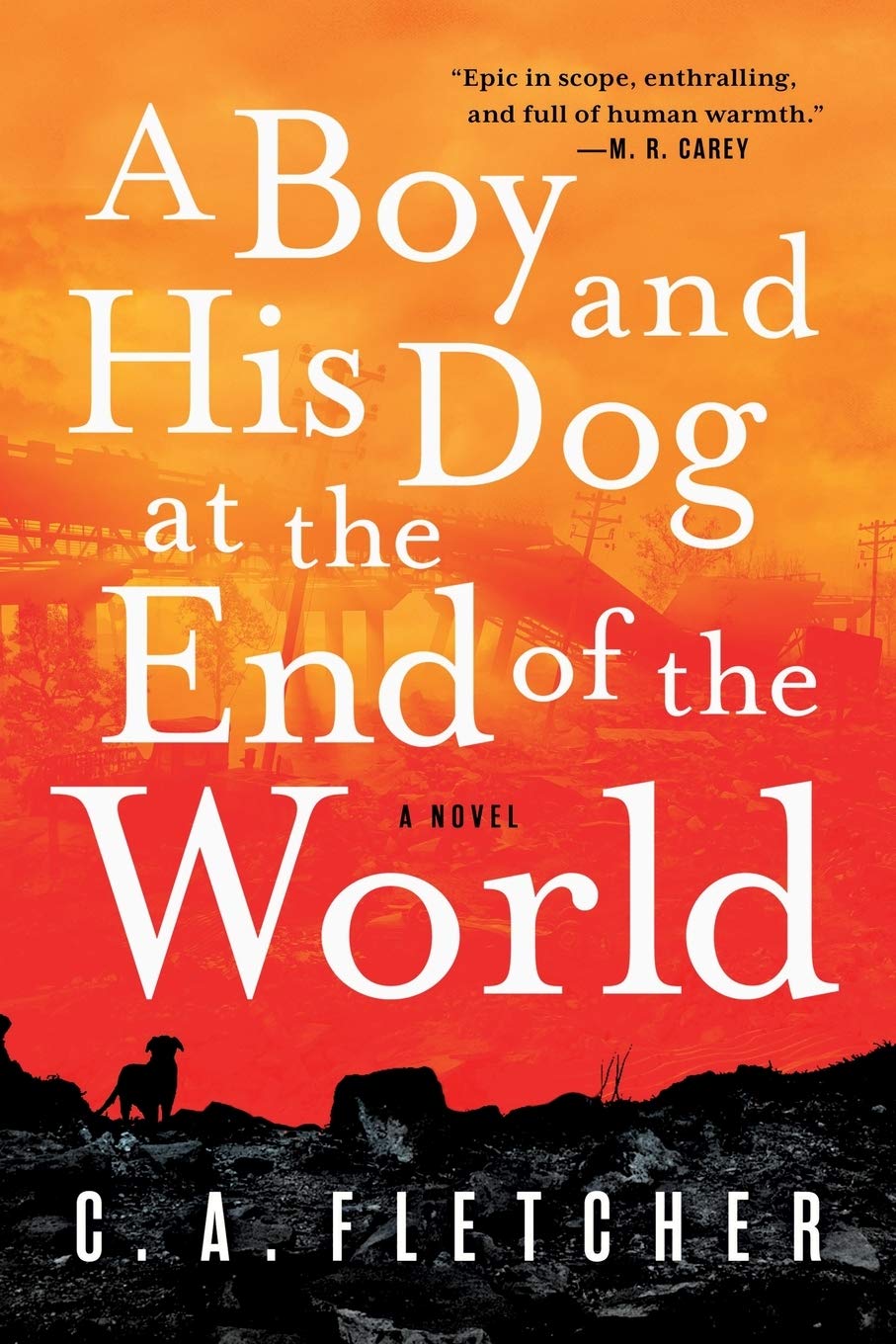

A Boy and His Dog at the End of the World by Charlie Fletcher

I love a good post-apocalyptic story, and Fletcher’s is a very good one indeed. Fletcher takes us to a Scottish isle a hundred years after the collapse of civilisation where one of the world’s last surviving families scrape and scavenge their way through what remains. When somebody sails away with one of the family dogs, Griz, the main character takes off after them. Things get a little rushed at the end, but it’s a well-told and evocative tale full of poignant reflections on the world that was.

There isn’t anything particularly Christian about Fletcher’ novel, but there was this:

There was a book on the shelves whose title caught my eye. It was called Surprised by Joy. It was partly the title that reminded me of my lost sister, and partly the name of the author whom I recognised because he had written books Mum had read to us when we were little. They were the kind I had liked, about a group of people on an adventure—children who went through a wardrobe and found a land of magic and talking lions and an evil ice witch. … We made a fire in the fireplace and sat with the windows open, watching the light die on the landscape below.

Metanoia by Anna McGahan

I know that God “does not show favouritism,” but there does seem to be a certain kind of passionate and unfiltered personality type that he likes to work with. King David and Simon Peter had it. I suspect Anna McGahan does too. Her conversion story is weird and wonderful. May God continue to fill her, and us all, “with the knowledge of his will in all spiritual wisdom and understanding, so as to walk in a manner worthy of the Lord.” Read more in Chris Swann’s review here.

Chinese Poems by Arthur Waley

I came across this book in a second-hand bookshop in a brief holiday between lockdowns this year. Arthur Waley (1899-1966) was a friend of the Bloomsbury set, an amateur Sinologist and orientalist and a poet in his own right. I can’t vouch for his translations of these ancient Chinese poems, but the final results are often moving. Some sound like Ecclesiastes; others make a sad contrast with Song of Songs. Here is a short sample from 9th century poet (and Tang Dynasty official) Bai JuYi:

On board ship: Reading Yuan Chen’s poems (c.816AD)

I take your poems in my hand and read them beside the candle;

The poems are finished: the candle is low: dawn not yet come.

With sore eyes by the guttering candle still I sit in the dark,

Listening to waves that, driven by the wind, strike the prow of the ship.